News & Publications

Trichomonas—Ancient Protozoan

January 1, 2014

By Felix Martinez, Jr., M.D.

Introduction

Trichomoniasis is the most common curable sexually transmitted disease today, more common than all bacterial sexually transmitted diseases combined.

Trichomonas is a genus of protozoans that are parasites of vertebrates. Parasites live in their infected host, co-opt its resources, and cause disease. Trichomonas vaginalis, the species that infects humans, lives in anaerobic conditions of the human urogenital tract.

The host-parasite relationship between Trichomonas vaginalis and humans is long-standing. We likely co-evolved with one another. A close relative of trichomonads has been shown in fossils to have caused ulcers in the jaw bones of tyranosaurad dinosaurs.

Trichomoniasis annually affects nearly 250 million men and women worldwide with more than seven million cases each year in the United States.1 Those infected with the parasite become especially vulnerable to other sexually transmitted diseases, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and human papillomavirus (HPV). In addition, complications from trichomoniasis include miscarriage, preterm delivery, low birth weight and infertility.

Some studies report that up to half of T. vaginalis infections in women are asymptomatic.2,3 Symptomatic infections present with symptoms of discharge (yellow, green or gray, sometimes frothy), odor, itching, and pain during urination and/or intercourse. Signs of infection may include small red ulcerations on the vagina and/or cervix, positive amine (whiff) test, and elevated vaginal pH.

Pregnant women with trichomoniasis are at increased risk for pre-term labor and delivery of low birth weight neonates.4,5

Pathogenesis

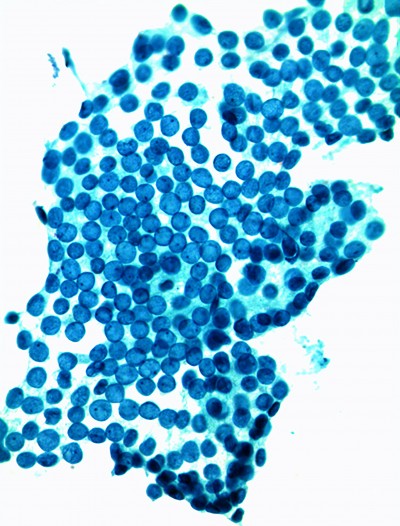

Scanning electron micrograph of Trichomonas vaginalis parasite adhering to vaginal epithelial cells collected from vaginal swabs. A non-adhered parasite is pear-shaped, whereas the attached parasite is flat and amoeboid. (Images courtesy of MicrobeWiki.com)

Trichomonas vaginalis is a pear-shaped organism which, when it sticks to the vaginal wall, flattens and dramatically increases its surface area. Scientists hypothesize that this trait brought a selective advantage during the microbe’s evolution. Its large cytoplasmic surface area, enabled by a puzzlingly huge genome, enables it to better colonize the area it is infecting. Trichomonas also shows predatory behavior by phagocytosis of lactobacilli and other native flora, making the vagina more alkaline and more hospitable for yet more trichomonads and other pathogens.

A large scientific T. vaginalis genome project for the first time identified pathogenic virulence factors called trichopores, some of which are secretery proteins which are capable of destroying vaginal epithelial cells.

Unique Mariner elements are another novelty found in the Trichomonas vaginalis genome research. Mariner elements are transposons -- jumping genes --which previously had only been found in animals and plants but never in protists.6

Trichomonas has four undulating flagella and a whip-like tail, organelles which impart quick, darting motility and which require large amounts of propulsion power. Driving energy for these organelles is provided by special cytoplasmic structures called hydrogenosomes, cytoplasmic elements that result in the production of hydrogen gas as a byproduct of metabolism. The release of hydrogen into alkaline vaginal secretions is responsible for the characteristic frothy discharge and fishy odor of trichomoniasis.

When infecting women, the parasite latches onto the vaginal surface by the formation of tendrils that project into the vaginal epithelium. The cytoskeleton of the protozoan has to change quite dramatically in order to accomplish attachment and requires large genomic input for the cytoplasmic signals and structural requirements are needed for attachment to occur.

Unique Bacterial Communities that May Promote Trichomonas Growth

A change in vaginal bacteria causes bacterial vaginosis, and women with this condition are at increased risk of acquiring trichomonas. Researchers have wondered if there are unique bacterial communities among women with bacterial vaginosis which would make women more susceptible to infection with trichomonas. Recent discoveries have shown that there are two bacteria very strongly associated with trichomonas infection. In part, what is special about the studied communities is high concentrations of two types of mycoplasma.

One discovered community resident was a completely unknown bacterium, recently named Mnola because it is a mycoplasma discovered in New Orleans, LA (hence, MNOLA) at LSU Health Sciences Center. Another is Mycoplasma hominis, a well-known bacterial pathogen.

The data indicate that women with trichomonas and the milieu of a mycoplasma-laden bacterial community suffer from worse disease than the other trichomonas infected women. They have greater amounts of discharge and redness of the vaginal wall. This group may also be at especially high risk for infection with HIV.

Especially interesting is evidence suggesting that trichomonas is responsible in some way for promoting these unique mycoplasma-dominated bacterial communities. Changing the paradigm about which comes first, vaginosis or vaginitis, certain microfloral ecosystems may not be colonizers that predispose a woman to infection but rather the result of a trichomonad farmer using the vaginal environment to cultivate bacterial communities that are in some way beneficial to trichomonas growth!7

A Virus Can Infect Trichomonas

Intriguingly, more than 80 percent of the parasites are themselves infected with a virus simply dubbed trichomonasvirus. Unlike flu viruses, this virus can’t spread by movement of free virions into a cell. Instead it spreads between cells when the trichomonas host cells divide or when they mate.

Trichomonasvirus seems to have no detrimental effect on the parasite, and the widespread occurrence of this virus has led researchers to suspect it might actually benefit the parasite in some way.

The virus does not infect the human cells, but it nonetheless aggravates the harmful effects of the parasite. These findings may explain why metronidazole may not prevent the harmful effects that trichomoniasis can have on a woman’s reproductive tract. In fact, metronidazole may possibly make the effects of trichomoniasis worse by the release of viruses from parasites killed by the drug.

Secondary inflammation might also help explain why the parasite could make its host vulnerable to other sexually transmitted diseases through destroyed or weakened barriers that normally protect against infection.

A virus-parasite symbiosis is felt to be the norm rather than the exception with this particular protozoan. Upwards of 80% of T. vaginalis isolates carry trichomonasvirus.

When antibiotic therapy is used with resulting aggravated symptoms, the dying or stressed protozoa may be releasing unharmed virions. Released virions then signal human cells to initiate an inflammatory response. This, in turn, might increase the danger that trichomoniasis poses to pregnant women and their fetus.

More research to better understand the viral cycle and the organismal structure of trichomonas that may make it vulnerable to drugs may lead to better treatment of trichomoniasis and related diseases.

PCR and tests using PCR-like methodologies can detect Trichomonas vaginalis with a sensitivity of 85-100%. 1

Detection / Diagnosis

Wet mount microscopy of a vaginal swab can yield highly specific findings, often revealing rapidly motile trichomonads and numerous white blood cells. Yet, wet mount identification of the organism seen by microscopy has a sensitivity of only 60-75%.3

| Study | PCR | Culture | Wet Mount |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wendel 8 | 94% | 28% | - |

| Hobbs 9 | 98% | 22.5% | - |

| Schirm 10 | 100% | 71% | 71% |

A cervico-vaginal swab can be submitted for laboratory testing to detect Trichomonas vaginalis by a variety of methods including culture and, now, molecular testing.

In offices that do not perform wet mount microscopy, patients with vaginal discharge or symptoms of vaginitis are sometimes empirically treated with a single oral dose of metronidazole because of the broad spectrum efficacy of the drug. Although this empirical approach can work, some T. vaginalis strains are resistant to metronidazole and, to avoid the difficult patient problem of persistent vaginosis/vaginitis, it really makes more sense to know specifically which organisms are present before beginning therapy.

Molecular Testing

Details of the first polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for T. vaginalis were published in 1992. Benefits of molecular testing include the use of highly sensitive and specific PCR or PCR-like technology, simple and convenient sample collection, and ambient temperature storage and transport. Since then, PCR and its derived technologies have quickly and repeatedly proved to be the most accurate diagnostic method for T. vaginalis detection. PCR and tests using PCR-like methodologies can detect T. vaginalis with a sensitivity of 85-100%.1 Several recent studies are reporting sensitivities and specificities approaching 100%. 10

At Incyte Diagnostics, trichomonas testing is performed using strand displacement and amplification technology (BD Viper).

Summary

We now know more than we have in the past about the prevalence of trichomonas and potential consequences of trichomonas infection, which can be asymptomatic and may have serious consequences if left untreated. Molecular testing is a very sensitive means of detecting trichomonas and offers significant advantage over wet mount microscopy and vaginal culture.

References

1 Schwebke JR, Burgess D. 2004. Trichomoniasis. Clin Microbiol Rev 17:794-803.

2 Fouts AC, Kraus SJ. 1980. Trichomonas vaginalis: reevaluation of its clinical presentation and laboratory diagnosis. J Infect Dis 141:137-143.

3 Krieger JN, Tam MR, et al. 1988. Diagnosis of trichomoniasis. Comparison of conventional wet- mount examination with cytologic studies, cultures, and monoclonal antibody staining of direct specimens. JAMA 259:1223-7.

4 Cotch MF, Pastorek JG 2nd, et al. 1997. Trichomonas vaginalis associated with low birth weight and preterm delivery. The Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Sex Transm Dis 24:353-60.

5 Minkoff H, Grunebaum AN, et al. 1984. Risk factors for prematurity and premature rupture of membranes: a prospective study of the vaginal flora in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 150:965-72.

6 Berman, J. Scientists crack the genome of the parasite causing trichomoniasis. NYU Langone Medical Center / New York University School of Medicine. Epub 2007 Jan 11.

7 “New Light Shed On Common Sexually Transmitted Infection”, Science Daily. Epub 2013 Apr 2.

8 Wendel KA, Erbelding EJ, et al. Use of urine polymerase chain reaction to define the prevalence and clinical presentation of Trichomonas vaginalis in men attending an STD clinic. Sex Transm Infect. 2003 Apr;79(2):151-3.

9 Hobbs MM, Lapple DM, et al. Methods for detection of Trichomonas vaginalis in the male partners of infected women: implications for control of trichomoniasis. J Clin Microbiol. 2006 Nov;44(11):3994-9. Epub 2006 Sep 13.

10 Schirm J, Bos PA, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis detection using real-time TaqMan PCR. J Microbiol Methods. 2007 Feb;68(2):243-7. Epub 2006 Sep 26.