News & Publications

Molecular Infectious Disease Testing on Vaginal Swabs

June 1, 2013

By Felix Martinez Jr, M.D.

In our world of rapidly evolving technology, does molecular testing for infectious disease offer value? If there is a current practice or test that detects disease and helps administer good care to patients, is there reason to readily adopt a new approach? Specifically, will molecular testing for specific organisms aid in the workup of vaginal discharge? Is this new testing a better mousetrap?

We ask these questions in the difficult clinical realm of vulvovaginitis/vaginosis and the new tests now available to identify organisms associated with these conditions. In evaluating whether to bring this new testing to Incyte Diagnostics, it was important for us to first understand exactly what the testing offers, as well as what, if any, changes that we might initiate would mean to our clients and their patients.

Vulvovaginitis/vaginosis affects many women and can be associated with several serious health conditions. Identifying a specific cause of some types of vulvovaginitis/vaginosis has remained enigmatic, and there is controversy and variation in the overall approach to this sometimes difficult-to-treat problem.

Many women who experience a vaginal infection have discharge, itching, and odor, which often continues after alternative therapies, including over-the-counter medications. In a small sample of self-diagnosed women who were studied, 34% had vulvovaginal candidiasis, 19% bacterial vaginosis, 21% mixed vaginitis, and 2% Trichomonas vaginitis. In the remainder, no disease was detected or involved a non-infectious condition (for example, lichen sclerosis)1.

This variety of causes and imputed causes of vulvovaginitis/vaginosis illustrates part of the problem that medical professionals face in trying to help patients with vaginal discharge and the difficulties encountered in selecting correct treatment choices.

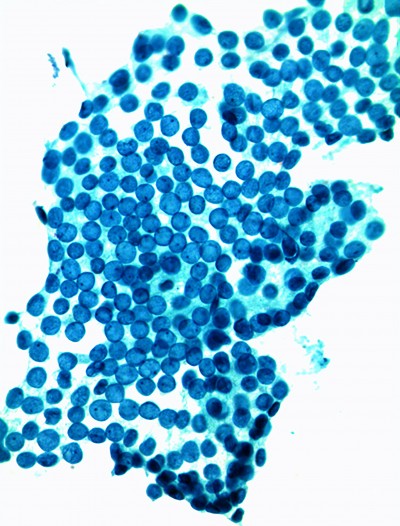

The three diseases most frequently associated with vaginal discharge are bacterial vaginosis (caused by the replacement of the vaginal flora by an overgrowth of bacteria, including Gardnerella vaginalis, Mobiluncus, Ureaplasma, Mycoplasma, and numerous fastidious or poorly characterized anaerobes), trichomoniasis (caused by the protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis), and candidiasis (genital fungal infection, usually caused by Candida albicans). In addition, cervicitis, both infectious and non-infectious, can also sometimes cause a vaginal discharge. Vulvovaginal candidiasis is usually not transmitted sexually, but it can be a frequent persisting condition in women who have vaginal complaints.

|

Table 1. Amsel Criteria for Diagnosis of BV: Three of the following four criteria must be met. Establishes accurate diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis in 90% of affected women. |

|

Homogeneous, non-clumping vaginal discharge |

|

Amine (fishy) odor when potassium hydroxide |

| Presence of clue cells (greater than 20%) on microscopy |

| Vaginal pH greater than 4.5 |

An important tool in evaluation of vaginal discharge has been wet mount microscopy. Wet mounts, however, require experience to interpret and are sometimes difficult to evaluate. Also, microscopes have become an expensive piece of office equipment that many offices have chosen to forego.

For patients presenting with vaginal discharge, many years of experience went into establishing criteria to narrow possible causes for discharge and subsequent patient treatment. Amsel criteria and Nugent’s scoring are excellent examples of criteria-based approaches to evaluate vaginal discharge.

Studies have shown, however, that Amsel criteria and wet mount microscopy have their own set of problems, and misdiagnosis can still occur using these time-tested approaches. In a study of the use of Amsel criteria and microscopy, it was found that the use of these measures and tools did not reduce the number of misinterpretations, and some studies reveal that the misdiagnosis of patients with vaginal complaints can be rather high.2

Other studies have shown inconsistent clinical recognition of Mycoplasma genitalium infection, with subsequent treatment failure and disease persistence due to employment of ineffective antibiotic use.3

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) analysis of vaginal swabs has proven to be a useful adjunct test for vulvovaginitis/vaginosis. Several improvements have been offered by this testing. First, the collection has improved by use of a flocked swab that is now available and that collects a sample from many areas on the vaginal wall, where flora is most abundant.

Another improvement has been the improved sensitivity and specificity of molecular testing. This allows for identification of specific organisms that respond to specific antibiotic therapy. Molecular testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia offer testing convenience when performed on a Pap collection, but samples obtained from the cervical area using traditional Pap collection devices may not offer the most sensitive means of collecting causative organisms of vulvovaginitis/vaginosis.

Incyte Diagnostics and UniPath offer vulvovaginitis/vaginosis testing on a selected group of organisms that fulfill the following selection criteria: bacteria that require different antibiotic treatment, organisms with higher odds-ratio scores for having an association with bacterial vaginosis, and organisms that are associated with cervicitis or non-gonococcal urethritis (for example, Mycoplasma genitalium).

Accurate speciation of identified organisms in this testing allows for appropriate treatment options and lower recurrence rates.

Incyte Diagnostics has chosen to offer Candida species testing as a separate test. Although approximately 90% of vulvovaginal candiasis is caused by Candida albicans, Candida glabrata is the second most frequent cause of candida vaginitis and can be difficult to treat because of developing resistance to azole compounds such as fluconazole. Candida tropicalis is also resistant to azole compounds. Candida glabrata and Candida tropicalis may become part of the normal mucocutaneous flora if the patient has a history of using azole compounds and may, thereby, not truly be pathogenic. Candida parapsilosis is an infrequent isolate from the vagina, and many strains of Candida parapsilosis are resistant to amphotericin B.

In summary, molecular testing has shown value in the evaluation of patients with signs and/or symptoms of vulvovagintis/vaginosis. The testing is both highly sensitive and specific. Speciation of organisms allows for selective employment of antibiotics, and a separate swab collection provides the best means to detect, identify, and speciate organisms.

The Incyte swab causes little discomfort and easily collects a generous sample over a large vaginal surface area, thereby improving sensitivity. For organisms that can infect without symptoms (for example, Trichomonas), molecular testing in selected populations will detect more patients harboring the organism. Otherwise, a separately collected vaginal swab in a symptomatic patient offers the opportunity to screen for a large variety of organisms and for selective antibiotic therapy.

So, if a better mousetrap does come along...

References:

1 Ferris DG et al. Over-the-Counter Antifungal Drug Misuse Associated With Patient-Diagnosed Vulvovaginal Candidiasis Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:419 –25.

2 Andreas Schwiertz*, David Taras, Kerstin Rusch and Volker Rusch. Throwing the dice for the diagnosis of vaginal complaints? Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials 2006, 5:4 doi:10.1186/1476- 0711-5-4

3 Weinstein S. A review of the epidemiology, diagnosis and evidence-based management of Mycoplasma genitalium. Sexual Health. 2011(8), 143-158